How Israel lost Hollywood: The changing face of western art on Palestine

How Israel lost Hollywood: The changing face of western art on Palestine

In the two years since 7 October, 2023, the most chilling, most unsettling video I came across was not directly related to the horrors in Gaza; of starving children or severed limbs.

It was a Guardian video report by Matthew Cassel shot in Tel Aviv in the summer and published last month.

In it, Israelis are seen cavorting the sunny beaches, shopping at bustling markets, and socialising in trendy coffee shops.

Cassel stumbles upon an anti-war demonstration only to realise that there’s scant mention of the Palestinians.

“Listen, Europeans and Australians are idiots,” an elderly Israeli participant shouts.

“They don’t understand that Islam is coming to them as well.”

All Israelis interviewed express little to no compassion for Palestinians killed and starved since 7 October while simultaneously disbelieving the veracity of images coming out of Gaza.

A young woman claims that 80 percent of those images are “staged”.

She makes mention of “Gazawood”, a term modelled after the derogatory “Pallywood”, which postulates that most images coming out of Palestine and Gaza have been manipulated to draw sympathy.

There is no mention of reports by countless human rights organisations dismantling the Israeli narrative and affirming the reality of Palestinian suffering.

Not one interviewee acknowledges the staggering numbers of civilian fatalities calculated by the Israeli military itself.

The “moral Israeli army”, as one soldier puts it, is blameless. And it all began on 7 October. But did it really? That’s a realisation now dawning on cultural institutions across the West.

‘Evil comes from failure’

Over the past couple of years, the one film referenced the most in relation to Gaza has been Jonathan Glazer’s The Zone of the Interest.

Most critics were reluctant to draw comparisons between the sinister indifference of the film’s unnervingly ordinary family leading a mundane life right next to Auschwitz and western apathy towards Gaza until Glazer made his famous 2024 Oscar speech.

“Indifference to evil is more insidious than evil itself,” the late Polish-American Jewish theologian Abraham Joshua Heschel once wrote. “It is a silent justification affording evil acceptability in society.”

What 7 October revealed is not this indifference to evil; what it revealed is that in the post-truth world, evil is the devising narrative to rationalise one’s indifference, prejudices and privilege.

"Evil comes from a failure to think... and for as soon as thought tries to engage itself with evil and examine the premises and principles from which it originates, it is frustrated because it finds nothing there,” Hannah Arendt famously said. “That is the banality of evil.”

If the aftermath of the war has proven anything, it’s that people are still willing to think, to challenge long-held unexamined narratives, to talk and debate and empathise and campaign for a just cause. And art was the centre of it all.

The immediate aftermath of 7 October was easily the most oppressive period I’ve experienced as an Arab writer and film professional.

Chaos and confusion after the Hamas attack gave way to the foreboding terror of Israel’s retribution.

Suddenly, the language used to engage with the subject became repressively limited.

A single misstep, a single misuse of any vague expression or syntax, could have ended a career in the free West.

We had to begin every statement by condemning Hamas to prove our righteousness; to prove that we hadn’t lost our morality in spite of the grave injustices every one of us bore witness to while coming of age.

In the West, every Arab was deemed suspect until proven otherwise.

Every artist and writer placed his career on the line by speaking out in those early days.

Time and time again, we had to underline our ideological differences with Hamas; our vehement opposition to the killing of civilians; our unquestionable rejection of any form of antisemitism; our unwavering camaraderie with our Jewish friends and colleagues and partners.

Every step of the way, we had to defend our basic humanity; every step of the way, we had to stand up to the dehumanisation every artist and writer faced when stipulating that 7 October did not occur out of sheer Jew hatred as the pro-Israel lobby repeatedly claimed it to be.

The story of Palestine has been documented to death in every conceivable medium by numberless academics, including Israelis, but people chose to remain blind to history; they chose not to think as Arendt put it.

From censorship to solidarity

In the aftermath of 7 October, western art and entertainment were not as kind to Palestine as they had been with Ukraine.

Hollywood immediately jumped to show its solidarity with Israel; art institutions and book fairs barred artists who publicly supported the Palestinian cause; and film festivals avoided the subject altogether.

This was the largest censorship campaign this writer has witnessed outside the Arab World.

The freedom of expression the West has perpetually paraded proved to be a myth, and that was before Trump made censorship the accepted norm in the Global North.

At the time, the well of racism that had been kept in check by diversity politics found a pretext to detonate its full ugliness.

The barrage of entertainment writings produced in those first weeks implicitly hinted that this was a war between the civilised Israelis and brute Arabs: between progressive Jews and their primitive Arab neighbours.

Then, changes in public opinion moved in tandem with the death toll amongst Palestinians and the increased awareness about their situation and cause.

The abiding thought throughout this exhaustive process was: did so many innocent people have to die before the world finally ventured to educate themselves about the subject?

A handful of artists and writers - Mark Ruffalo, Javier Bardem, Susan Sarandon, Melissa Barrera, Bella Hadid, Dua Lipa, Nan Goldin, Annie Ernaux - were quick to show their solidarity with the besieged population of Gaza.

Scores of other celebrities who joined the movement only acted when Gaza was officially declared a genocide by humans right groups and states, that is, when the Israeli aggression could no longer be justified.

It's unclear to what extent the celebrity endorsement may have influenced public perception of the Palestinian cause, but it certainly gave it a widespread recognition that has been absent for the past half century.

Vanessa Redgrave was a lonely voice when she denounced the intimidation and bullying of “the Zionist hoodlums” in her blistering 1978 Oscar speech.

An opening for Arab voices

The post 9/11 culture forced a change in how Arabs and Palestinians are represented in western art.

Outright demonisation and exoticisation of Arabs in the aftermath of the attacks has faltered as more space has been opened over the past two decades to encompass and understand Arab stories.

Palestinian stories have become staples in American and European cultures. On TV, Mo and Ramy succeeded in presenting the Palestinian narrative to a wider audience.

The pro-Zionist lobby in entertainment has grown increasingly marginalised and ostracised

Independent Palestinian films have secured ample funding from European institutions and have figured in some of the world’s biggest festivals.

Writers, musicians, and visual artists have become staples in any serious culture scene.

The fallout of 7 October may have derailed Palestinian artists in the first year after the Hamas attack but in October 2025, the picture looks starkly different.

More and more artists and musicians and celebrities have been speaking out against Israel.

Palestinian authors - Yasmin Zaher, Basim Khandaqji, Mosab Abu Toha, Lena Khalaf Tuffaha - have been garnering accolades from the world’s most prestigious associations.

Palestinian flags and the watermelon pin have become a familiar sight in music festivals on both sides of the Atlantic.

More and more Hollywood stars have been backing Palestinian films, such as Ruffalo and Bardem with Cherien Dabis’s All That’s Left of You; Brad Pitt, Joaquin Phoenix, Rooney Mara and Alfonso Cuaron with Kaouther Ben Hania’s The Voice of Hind Rajab.

No Other Land became the first Arab story to win an Oscar; its $2.5m box office take has made it the highest grossing Arab film in North America.

Two years after 7 October, Redgrave, who was loudly booed at the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion, is no longer a stray voice.

The pro-Zionist lobby in entertainment, meanwhile, has grown increasingly marginalised and ostracised.

Dirty money

The pendulum has acutely swung towards the Palestinian cause. Favourable opinion of Israel is at a historic low according to polls in most of the world, including the US and Germany.

Cultural institutions remain reluctant to shun their Israeli counterparts, but there’s a noticeable reduction in collaboration with state-backed Israeli artists.

This momentous wave would not have materialised if not for the countless protests and unwavering grassroot movements that engulfed the western world.

Art, entertainment, and Hollywood have been transformed into reactionary industries playing catch-up to the enlightened youth.

This sweeping change in ideology was not of their initiation…it was the will and conviction of the people that spearheaded it.

Could Gaza incite a seismic shift in arts and entertainment? The jury remains out on that.

Of the copious Gaza-related political statements made in last month’s Venice Film Festival, the statement by American actress and longtime Palestine supporter Indya Moore regarding the ethical duty of investigating the source of funding particularly hit a chord.

“The head agent was trying to persuade other agents to drop me because of my advocacy around Palestine.”

— Middle East Eye (@MiddleEastEye) August 5, 2025

US actor and model Indya Moore on the silence in Hollywood around Gaza, and what happens when you speak out.

Watch full interview ➡: https://t.co/OAyBuBdQP0 pic.twitter.com/M9xDppIvRu

Funding in arts and entertainment has always been a thorny and complex subject, more so in cinema which relies on a multitude of sources and disparate financiers.

Dirty money has been integral to film production across different generations in every continent.

Critics and film insiders have accepted it as an unavoidable reality of the medium.

If money from shady or ethically questionable funders is used to produce great art that counters what these financiers stand for, then what’s the harm?

Yet the backlash that faced indie streaming company Mubi regarding its partnership with Sequoia Capital which has close ties with the Israeli military is bound to raise more inquiries about the ecosystem of film financing.

Israel is the easiest target to pin down, but what about China or Saudi Arabia? What about anti-union American corporations with exploitative working conditions? What about public grants from states that have been complicit in the Gaza genocide like Germany?

And when it comes to programming, is it kosher to support films bankrolled by state-funded autocracies like Egypt or Iran?

Israel, by comparison, is a clear-cut case. But if we want a healthier and more ethical industry, these difficult, more muddled questions need to be asked.

What now for Palestine in film?

The Palestinian narrative has never been as ubiquitous as it is now, but the parameters of expression remain narrow. Gaza, the Nakba, and the colonialist settlements are the most commonly accepted themes of post-7 October Palestinian stories.

Films that wish to tackle “thorny” issues like armed resistance, queer rights, or corruption of the Palestinian Authority might find grave resistance from both funders and an audience unwilling to take in stories with more nuance and dimensions.

Pictures in the vein of Hany Abu-Assad’s Paradise Now (2005) with its sympathetic view of suicide bombers, Elia Suleiman’s Divine Intervention (2002) with its comic depiction of violent assault on the IDF, or even Tewfik Saleh’s classic The Dupes (1972) with its damning indictment of Arab states for their abandonment of the Palestinian cause, have no chance getting financed or exhibited anytime soon.

The same goes with Muayad Alayan’s The Report on Sarah and Saleem (2018) or Maha Haj’s Mediterranean Fever (2022) with their frank portrayals of broken Palestinian lives inside Israel.

It might be too soon to have more films of Paradise Now and Sarah and Saleem’s ilk, but as the Palestinian narrative grows more familiar and popular, there will be an inevitable demand for richer, more multifaceted narratives expounding the fullness of Palestine’s past and present.

What is the Nakba?

+ Show - HideThe Nakba is one of the key events in modern Middle East history and one that has come to define the Israeli-Palestinian conflict ever since.

Also known as "The Catastrophe", it began in late 1947 and 1948, as the new state of Israel came into existence.

Palestine was part of the Ottoman Empire for hundreds of years until it was captured by the UK at the end of World War One (1914-18).

The League of Nations - a forerunner of the UN - gave Britain a "mandate" over Palestine after the war, which did not take into account the wishes of the native Palestinian population.

The aim of such mandates was to bring about "the rendering of administrative assistance and advice" to native populations until they were deemed capable of standing alone as independent states.

What was the problem?

The British Mandate incorporated the Balfour Declaration, sent by Arthur Balfour, the British foreign secretary, to Lord Walter Rothschild, a prominent member of the British Jewish community, in 1917.

It pledged to establish "in Palestine a national home for the Jewish people", who made up less than 10 percent of the population at the time.

During the mandate years (1923-48), the UK facilitated the immigration of European Jews to Palestine, increasing their population 10-fold, from 60,000 in the pre-Mandate era to 700,000 by 1948.

They also trained, armed and supplied Zionist groups, and allowed them a degree of self-governance.

In contrast, the native Palestinian population, which rejected European Jewish immigration and called for independence, was violently suppressed.

The number of Jews arriving in Palestine from Europe and elsewhere increased in the wake of the Holocaust, which systemically targeted Jews and others, resulting in the deaths of more than 6m people.

In February 1947, Britain announced it would terminate the mandate and turn the question of Palestine over to the newly formed United Nations.

The UN adopted a partition plan in November 1947, which divided Palestine into two parts: 55 percent would form a Jewish state, while 45 percent would create an Arab state. Jerusalem would be kept under international control.

But many argue that the plan did not take into account populations at the time.

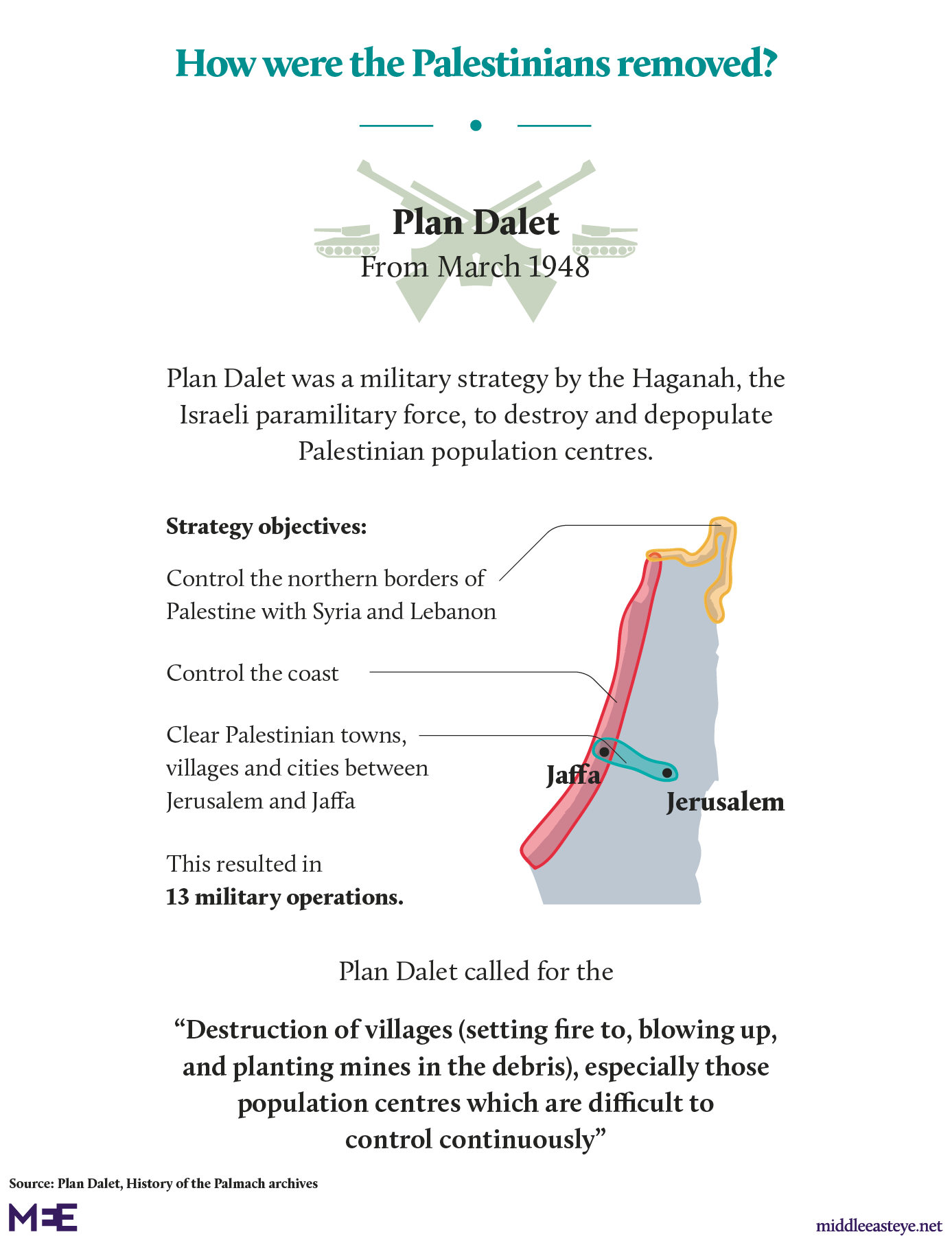

In addition, Jewish paramilitary groups produced a strategy to control the borders of the new territory, called Plan Dalet (below).

Some of their members would go on to become key Israeli leaders, including Yitzhak Rabin (prime minister 1992 - 1995), Ariel Sharon (prime minister 2001 - 2006) and Moshe Dayan (minister of defence 1967 - 1974).

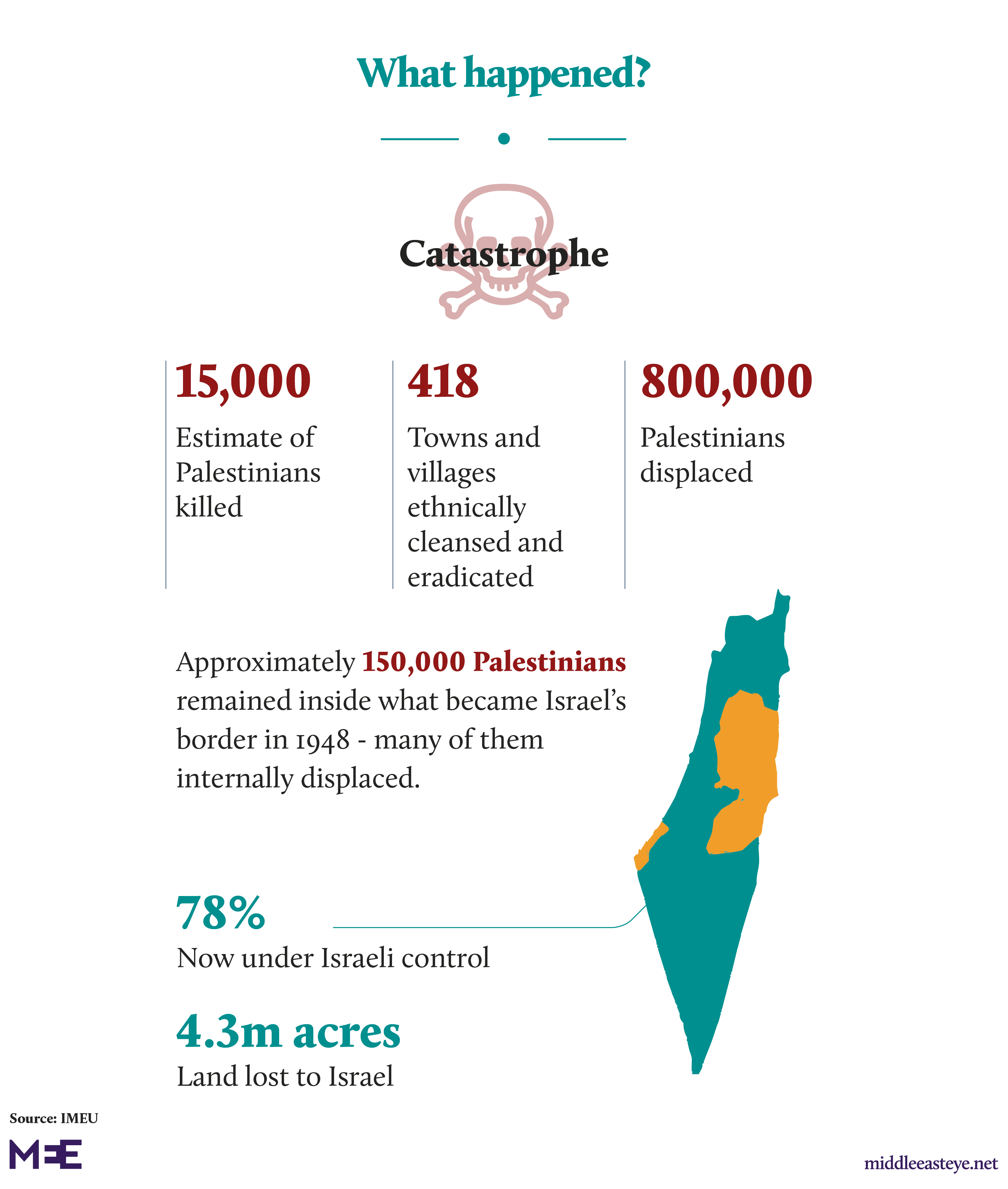

In the weeks and months that followed, thousands of Palestinians were killed or driven from their homes and communities uprooted by Jewish paramilitary groups.

Jews were also killed by Palestinian groups, if not in the same numbers.

On 14 May 1948, the State of Israel was unilaterally declared, a day before the British Mandate officially expired.

The new state had increased its share of historic Palestine from 55 percent to 78 percent. The remaining 22 percent was under Arab control.

Many of the Palestinians who fled or were driven from their homes never returned to historic Palestine. Much of it is now the modern-day state of Israel.

More than 70 years later, millions of their descendants live in dozens of refugee camps in Gaza, the West Bank, and surrounding countries, including Jordan, Syria, and Lebanon.

Many still keep the keys to the homes that they and their families were forced to leave.

Nakba Day is now a key commemorative date in the Palestinian calendar. It is traditionally marked on 15 May, the date after Israeli independence was proclaimed in 1948.

Some Palestinians also observe it on the day of Israeli independence celebrations, which itself changes from year to year due to variations in the Hebrew calendar.

All of this is to say that the Palestinian narrative is here to stay. The art and entertainment landscape looks unrecognisable now compared to before 7 October.

The power of empathy, love, and knowledge has shown that there’s a light at the end of the tunnel.

In The Ethics of Ambiguity, French philosopher Simone de Beauvoir writes: “A freedom which is interested only in denying freedom must be denied.”

The freedom the Zionist state has enjoyed to tell its distorted, polished version of its foundation since 1948, the freedom it has enjoyed to suppress the Palestinian narrative for more than 75 years, may finally be coming to an end.

The Palestinian narrative no longer has a place for victimhood. As Ghassan Kanafani once put it, the Palestinian cause “is a cause for every revolutionary, wherever he is, as a cause of the exploited and oppressed masses in our era.”

The indifference of the Israelis in the Guardian video is no longer the norm...it’s now the exception.