Fifty years of plunder: How Morocco and its allies profit from Western Sahara

Fifty years of plunder: How Morocco and its allies profit from Western Sahara

In late October 2020, Minatu Ljatat travelled from her home in the refugee camp of Awserd in southwestern Algeria to Guerguerat in the occupied Western Sahara.

The area is known to some Sahrawi activists as the “plunder corridor”, because it contains the only route through which Morocco can export products from the territories it controls in Western Sahara.

As such, for many Sahrawis, Guerguerat has become a symbol of the increasing impunity Morocco enjoys internationally in exploiting the natural resources of their homeland, which was conquered by the kingdom 50 years ago.

Ljatat was part of a group of around 200 activists from her camp who travelled through territory controlled by the Polisario Front, Western Sahara's national liberation movement, to the Guerguerat crossing with the aim of setting up a camp to block the traffic passing through it.

“It was a very peaceful protest. We were saying that we just want our home, we want just a free Western Sahara,” she told Middle East Eye at her home in Awserd.

The group built tents and settled there for several weeks, and stopped traffic, including trucks of fish caught in the Atlantic off the coast of Moroccan-occupied Western Sahara. Then, on 13 November, Morocco launched an operation to remove them.

In response to Morocco’s attacks on the protesters, the Polisario Front called off a ceasefire that had been in place since 1991.

Since then, numerous foreign companies - including French, Spanish, Israeli and US - have stepped up their collaboration with Morocco to extract the resources of the Western Sahara, and, through their investments in a booming renewables market, have been accused of “greenwashing” the kingdom’s actions.

Despite partially successful challenges in the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU), many Sahrawis feel they have few options left.

Ljatat, who fled her home in Western Sahara in 1976, said that after so many years of a peace process that had resulted in nothing for the Sahrawis, while Morocco continued to exploit their lands and repress those still living inside the occupied territories, she wanted to see armed struggle resume.

“We were hopeless… nobody's doing anything. So we started asking the government [of the Polisario-run Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic] to restart the war,” she said.

“I don't want anyone to be killed, I don't want civilians to be killed. War, as you know, costs a lot, costs everything sometimes. But if that is the only solution, I am with it.”

The last colony in Africa

Western Sahara is often referred to as the last colony in Africa and is included in the United Nations list of Non-Self-Governing Territories.

The territory is officially, legally, recognised as being under Spanish jurisdiction by most of the international community, as the former colonial power failed to finalise a UN-mandated independence process and instead allowed Morocco and Mauritania to invade from north and south, overriding the wishes of Sahrawi independence campaigners.

‘European involvement in fishing, phosphate extraction and other resource deals… grants legitimacy to a reality founded on occupation’

- Mamine Hachimi, Sahrawi journalist and filmmaker

Fifty years ago, on 6 November 1975, Morocco’s King Hassan II sent 350,000 people to the border of Western Sahara, before entering into the territory in what became known as the Green March.

By 1979, after fighting involving the Polisario Front and Mauritania, Morocco was left as the sole power controlling the region.

There then followed several more decades of fighting between Morocco and the Polisario Front, which had taken control of the part of Western Sahara occupied by Mauritania after the Spanish withdrew.

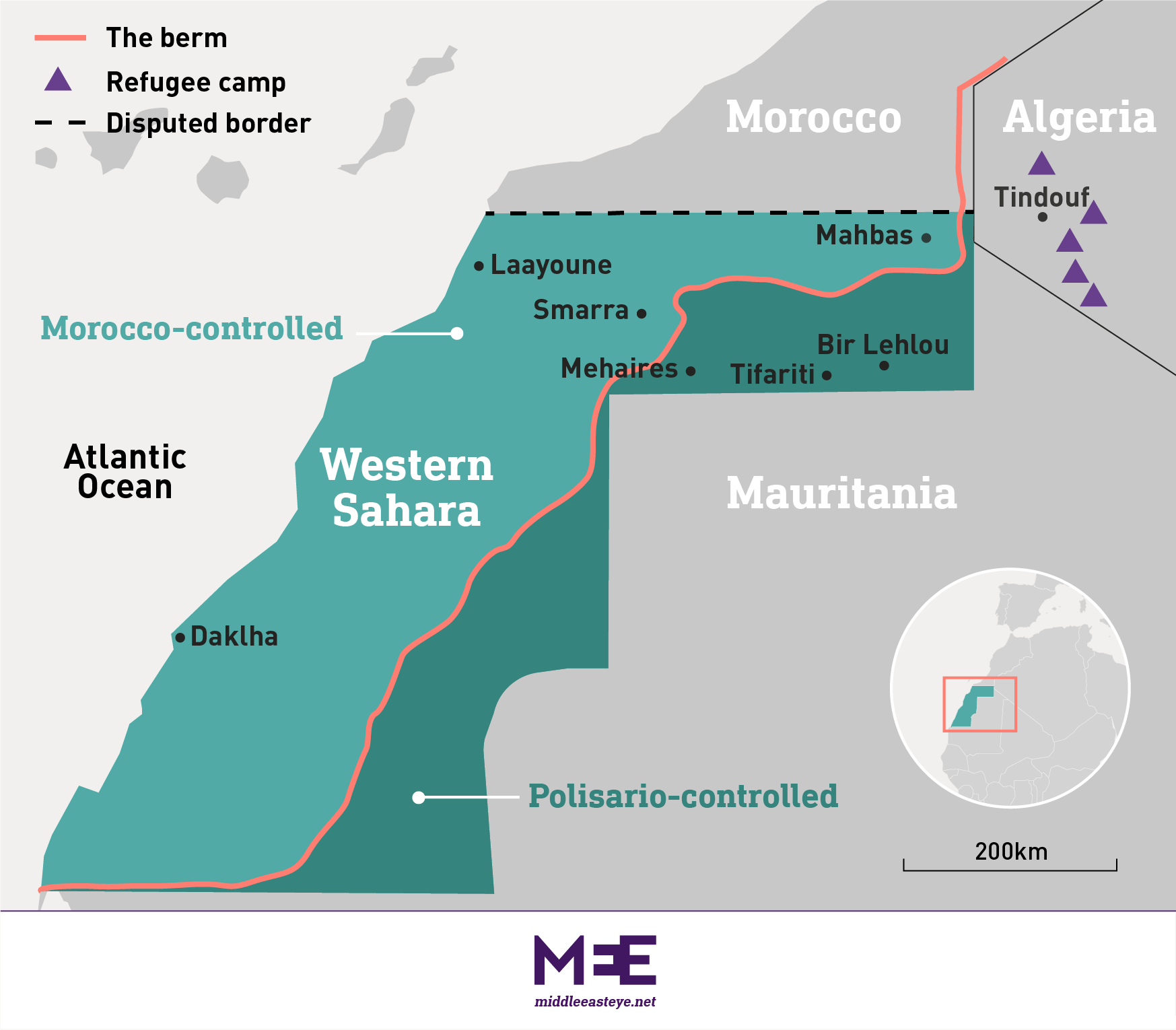

Starting in 1980, Morocco began constructing the berm, a fortified sand wall that runs down Western Sahara, separating areas held by the kingdom and the 20 percent of the territory nominally controlled by the Polisario Front, which is backed by Algeria.

Sahrawi activists living in the territories occupied by Morocco have faced fierce repression – with female activists in particular suffering sexual abuse and violence at the hands of police – while the hundreds of thousands living in refugee camps in Algeria continue to endure lives dependent almost entirely on UN and Algerian support in the harsh desert environment.

“Sahrawi refugees are refugees of a cause, not refugees of famine or natural disaster,” Oubi Bouchraya Bachir, the Polisario Front's former representative in Geneva, told MEE.

“The reason for their refuge - namely occupation – still exists.”

In 1991, after as many as 20,000 people had been killed on both sides, a ceasefire was declared. That was supposed to be followed by a referendum the next year on independence for the Sahrawis. But there has been no such referendum, and with the collapse of the ceasefire in 2020, European states and corporations have rapidly increased their investment in the territories occupied by Morocco.

That same year, the US also broke with decades of policy as President Donald Trump agreed to recognise Moroccan claims of sovereignty over the territory in exchange for the North African kingdom normalising relations with Israel, a move that the Biden administration did not reverse.

Since then, Sahrawis have been involved in numerous legal battles to challenge the increasing involvement of foreign companies in the occupied territories.

Sahrawi journalist and filmmaker Mamine Hachimi, originally from the city of Laayoune in Morocco-controlled Western Sahara and now living in France, said it was “morally unacceptable”.

“European involvement in fishing, phosphate extraction and other resource deals – often negotiated with Rabat without the consent of the Sahrawi people – grants legitimacy to a reality founded on occupation,” he told MEE.

Foreign exploitation and ‘greenwashing’

In 2001, Morocco granted oil exploration licences to a number of foreign companies for areas in offshore Western Sahara.

The move provoked outcry from Sahrawis and led to an unprecedented legal opinion issued by the UN Security Council the following year, which established that Morocco would have no right to engage in further oil exploration in Western Sahara without the consent of Sahrawis.

Nevertheless, investment and development in the region moved forwards, and while oil and gas exploration continues – with Israel's NewMed Energy and Morocco's Adarco jointly granted a licence to explore and produce oil and gas off the coast of the city of Boujdour – a range of other resources have taken centre stage.

‘[Morocco is] cementing the occupation internationally in creating political dependency of foreign states to the territory’

- Erik Hagen, Western Sahara Resource Watch

In 2000, the EU-Morocco Association Agreement came into force, creating a free-trade area and liberalising a two-way trade in goods.

While the region possesses some of the world’s highest quality phosphate reserves and rich fishing banks, the monitoring group Western Sahara Resource Watch (WSRW) says it has been the exploitation of green energy that has been most “horrible” for the Sahrawis.

The biggest and most “problematic” of the ongoing projects is the construction of a major, wind-powered desalination plant north of Dakhla that has been touted as providing “climate resilience” in an increasingly water-scarce region.

Constructed as a private-public partnership between Morocco's Nareva, which is owned by King Mohammed VI's holding company, and French company Engie, the project is set to produce 37 million cubic metres of drinking water annually, with the majority being used to irrigate 5,000 hectares of farmland.

Apart from being built on occupied land, WSRW warns that the new project – which will produce goods sold predominantly in the European Union – will move Moroccan farmers and workers to the territories, driving further demographic change in the region.

Meanwhile, the Casablanca-Settat desalination project, which is projected to become the largest of its kind in the world, is based in Morocco but is set to be powered by the 360MW Bir Anzarane wind farm in occupied Western Sahara.

Set to be fully operational by 2028, it's being built by a consortium of Spanish conglomerate Acciona and two Moroccan firms, with Spain contributing roughly €340m ($395m) out of an investment of €613m ($712m).

Neither France nor Spain recognises Morocco’s sovereignty over the Western Sahara, though both have expressed support for Morocco’s controversial 2007 “autonomy plan”, which envisions the territory as self-governing under Moroccan sovereignty and is rejected by Algeria and the Polisario Front as illegal.

The move was seen as aiming to normalise the two European countries’ increasing involvement in construction and exploitation of the territory.

The extraction of phosphate, another key industry in the Western Sahara, by the Moroccan state-owned phosphate company OCP is also 100 percent derived from energy produced in the occupied territory, generated by 22 wind turbines produced by German company Siemens Energy at the 50 MW Foum el Oued wind farm.

MEE contacted Engie and Acciona for a statement but received no response.

In a statement to MEE, Siemens Energy said: “With our engineering solutions in the field of renewable energy, we strive to counteract the effects of the climate crisis. We are aware of the complex political situation in Western Sahara and are committed to upholding human rights standards.

“As a supplier, we work to ensure that customer projects in Western Sahara respect the rights of the local population. We review all potential projects on a case-by-case basis to ensure that the requirements of the European Court of Justice are met. Our goal is to make a positive contribution while taking into account the complex circumstances in the region.”

'Implicate Russia in activities in the Sahara, as is already the case in the field of fisheries'

- Moroccan diplomatic memo

WSRW board member Erik Hagen said Morocco was fundamentally engaged in “greenwashing” – laundering its reputation and its grip over the Western Sahara through its promotion of supposedly ethical and environmentally conscious energy.

“It's cementing the occupation,” Hagen told MEE. "Morocco is making itself dependent on energy produced in Western Sahara for its own industries and population. And it's cementing the occupation internationally in creating political dependency of foreign states to the territory.”

A Moroccan diplomatic memo leaked in 2014 appeared to show Morocco quite openly admitting the political implications of its actions.

Discussing growing relations between Morocco and Russia, the document stressed the need to “implicate Russia in activities in the Sahara, as is already the case in the field of fisheries”.

“Oil exploration, phosphates, energy and touristic development are, among others, the sectors that could be involved in this respect,” it read.

And then “in return, Russia could guarantee a freeze on the Sahara file within the UN, the time for the Kingdom to take strong action with irreversible facts with regard to the ‘marocanite’ [‘Moroccanness’] of the Sahara".

Legal challenges

In 2012, in an apparent change of tactics, the Polisario Front started challenging the occupation in the CJEU. This led to repeated rulings asserting the group’s status as the representatives of the Sahrawis and the need for their consent in trade deals agreed in the territory.

In 2015, the court annulled the EU-Morocco agriculture agreement “in so far as it applies to Western Sahara”, a ruling appealed by the EU Council.

Despite repeated appeals, the CJEU has issued numerous rulings supporting the Polisario Front’s arguments and the principle that the Western Sahara represents a distinct territory from Morocco.

In early October, the EU and Morocco concluded an amendment to the EU-Mediterranean Agreement on tariffs on products originating in the Western Sahara.

The amendment was pushed through by the EU Commission without scrutiny by the parliament, provoking anger and an emergency session from left-wing MEPs.

Much of the criticism focused on the amendment’s assurance that the “implied consent” of the Sahrawis had indeed been achieved and that the Sahrawis would benefit both as a result of the production of renewables and through increased EU aid to refugees in Algeria.

Another aspect was a reference to labelling products based on their region of origin by using Morocco’s own designations (“Laayoune-Sakia El Hamra” and “Dakhla-Oued Eddahab”) rather than “Western Sahara”, or making no reference to the territory being occupied - which stands in contrast to the EU’s policies on products originating in the occupied Palestinian territories, which must be labelled as such.

Hagen branded the new amendment “insane”.

“It’s completely sidelined the parliament and the member states and the Sahrawis and the court – and even the rules of origin declaration aspect of it makes absolutely no sense,” he said.

“It opens up [the prospect] for no longer having countries of origin, but regions of origin – it's like it's creating a whole new universe just for the sake of Western Sahara in Morocco.”

Hachimi said that it was up to ordinary citizens to take action if national governments continued their complicity in the exploitation of Western Sahara.

He cited the various campaigns launched by pro-Palestinian activists against Israel’s occupation of their lands.

“Boycotts, divestment and sanctions are peaceful tools aimed at enforcing international law and ending injustice,” he said.

“If the world supports the BDS movement against Israel to end occupation and oppression, the same ethical and legal principles apply to the case of Western Sahara.”

Bachir said that Western Sahara solidarity activists are developing a programme similar to the Palestinian BDS but adapted to the different context.

“There is talk of protesting and raising awareness among European consumers about goods that are marketed with false labels regarding their country of origin and are produced in the context of military occupation and gross human rights violations,” he told MEE.

The ‘reality that didn’t come’

Last month, the Polisario Front presented a new proposal at the UN in New York for a solution to the conflict.

In the proposal, the group expressed its willingness to open negotiations with Morocco "to reach mutually acceptable provisional arrangements that would preserve the current economic interests of the Kingdom of Morocco and any other third parties relating to the natural resources of Western Sahara".

It added that while it did “not need to abandon its dream of Sahrawi self-determination”, it needed “to rethink how self-determination can best be achieved given the current geopolitical realities”.

‘I’m full of hope that maybe in the future we will have our free Western Sahara. Our legitimate right to live there, to be there, to exist there’

- Minatu Ljatat, Sahrawi refugee

Last Friday, the UN Security Council adopted, at the initiative of the United States, a resolution providing significant support for the Moroccan position by calling upon the parties to take the 2007 “autonomy plan” as a basis for negotiations.

The Council said that “genuine autonomy could represent a most feasible outcome”, with a view to achieving “a final and mutually acceptable political solution that provides for the self-determination of the people of Western Sahara”.

The delegate from Algeria, which did not participate in the vote, criticised the text for not faithfully reflecting the UN doctrine on decolonisation and falling short of the legitimate aspirations of the Sahrawis by prioritising one option over others.

The Polisario Front also rejected the resolution, saying that “it would not be party to any political process or negotiations based on any proposals which aim to legitimise Morocco’s illegal military occupation of Western Sahara and deprive the Sahrawi people of their right to self-determination and sovereignty over their homeland”.

Polisario Front maintains that any solution would require a referendum to be put to the Sahrawi people, something Morocco has long resisted.

“The Polisario is ready for negotiation and dialogue, but not within a pre-determined framework and with a pre-determined outcome,” Bachir told MEE.

“We have a clear mandate as a national liberation movement to lead our people towards the exercise of their right to self-determination, and we cannot engage in any process outside the genuine exercise of self-determination in accordance with the principles and the charter of the United Nations.”

Hagen told MEE the current state of affairs represented a “paradox” in the conflict.

“The two parties, each of them, have good cards in their hands: Morocco has the power and Polisario has the law. And those two cards are getting stronger and stronger,” he said.

Regardless of the ongoing legal challenges, Moroccan development in the region is accelerating.

Last month saw the opening of a new border crossing in the Amgala region of Western Sahara.

It aims to connect the city of Smara to Bir Moghrein in Mauritania via a new 93km road, providing another land route for the transfer of products and resources out of the occupied territory for international export.

King Mohammed VI has described the Amgala crossing as a cornerstone of his “Atlantic Initiative”, which he says is designed to provide landlocked Sahel countries with access to the Atlantic Ocean.

While the fighting between Morocco and the Sahrawis continues, both through asymmetric armed conflict in the occupied territories and in the courts, there is little indication that the kingdom is slowing its mammoth development projects in Western Sahara.

Ljatat, whose age and an injured knee have limited her ability to take part in further activism, said she had been “extremely disappointed” at the lack of progress since she first travelled to Guerguerat in 2020.

“I am sad for that reality that didn't come… and didn't give us what we were expecting,” she said.

“But at the same time, I’m full of hope that maybe in the future we will have our free Western Sahara. Our legitimate right to live there, to be there, to exist there.”